Nat Chioke Williams, Executive Director, Hill-Snowdon Foundation

The tragic killing of an unarmed African American teenager, Michael Brown, by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri gave a new energy and national platform to the issue of police brutality and excessive force in the Black community. Indeed, in the months surrounding Mike Brown’s killing, there was a wave of killings of unarmed Black men, boys and women by white police officers across the country including Ezell Ford in Los Angeles; John Crawford, Tamir Rice and Tanisha Anderson in Ohio; and Eric Garner and Akai Gurley in NY1. To date, only one of the police officers involved in these shootings has been indicted. This is not a new phenomenon, as black men, boys and women have been killed by law enforcement under suspicious or seemingly criminal circumstances for generations without prosecution or conviction. The recent release of the movie Selma is a timely reminder of the history of excessive force by police against the Black community and also the legacy of brutality, repression, disenfranchisement and unequal treatment of Black people codified into the law and institutional practice of this country.

However, this time seems different. Under the banner of Black Lives Matter, a new social consciousness and mass action has arisen that has shocked the status quo out of its complacent and complicit comfort zone. The Black Lives Matter movement has allowed the country to approach having honest, clear and urgent dialogue on structural racism by punching holes in the cone of silence that typically suffocates meaningful dialogue on racism with a sea of deeply cynical memes like political correctness, reverse racism, and color blindness. The Black Lives Matter meme is powerful because it resonates so deeply across the spectrum of the Black community – from a 14 year old protestor in Ferguson, to a 93 year old grandmother in Georgia, to a trans woman in Los Angeles, to a fast food worker in Boston, to a returning citizen in Louisiana, to the President of the United States. It simply captures our enduring reality that even though we have made progress, on average Black lives still do not matter as much as White lives as a matter of institutional policy and social practice.

At first blush, this may feel like a provocative statement. But the naked truth of our world is that although all lives matter, some lives matter more than others. In our world and in our country, the rich matter more than the poor; men matter more than women; citizens matter more than non-citizens; heterosexuals matter more than gays and lesbians; soldiers and police officers matter more than civilians; and yes White people matter more than Black people. The relative worth of different classes of people can be seen in how laws, institutional policies and practices are implemented differentially. For instance, the rich get preferential treatment in tax policy; men get paid more than women for the same work; same sex couples still have to fight for the right to marry and the associated legal protections; police tend not to get indicted for killing civilians, etc. Another example is the gutting of the Voting Rights Act by the Supreme Court and the slew of voter suppression laws that were designed to have a disproportionately negative impact on the Black community. One of the most blatant and significant political enshrinements of Black lives mattering less than White lives is found in Article 1, Section 2, Paragraph 3 of the United States Constitution, commonly known as the “three-fifths compromise” that defined the value or worth of those in bondage (largely enslaved Blacks) as only three fifths of free people (almost entirely White). Even after the 13th Amendment abolished slavery in the Union territories in 1864 and the 14th amendment specifically negated the three fifths compromise, there were countless laws, provisions, policies and practices in every jurisdiction of this country, including at the federal level, that established an enduring legacy that defined White lives as more precious than Black lives and that Black people deserved to be treated worse.

So if we accept the basic fact of life that some lives do actually matter more in this society, then what determines a particular group’s social worth and as an extension, what will help make Black lives matter more? The answer to this question is complex and multi-layered, but when you boil it all down the answer is power. Those groups that have more political, institutional and economic power have greater social worth and matter more than those who have less power. By political power I mean the capacity to define and impact public policy and institutional practice and the ability to levy or exact a consequence for unwanted actions. Political power is exercised through strong and dynamic institutions and organizations; thus to have political power you need to have powerful institutions. It is important to note that I am not talking about an individual’s social worth (e.g., Oprah Winfrey or President Obama), but the disparate treatment of whole social groups as reflected in public policy, institutional practice and social regard. This is an important point because a common tactic of those opposed to Black social change is to highlight the achievements of the few to delegitimize the structural deprivations experienced by the Black community.

Therefore, in order to make Black lives matter more, the Black community needs to build enough political and institutional power to significantly change both policy and public perception and to directly challenge and dismantle the structural racism that defines perpetual Black social, political, economic inequity. This would involve building and strengthening the institutional and organizational infrastructure necessary to effect broad social change; re-prioritizing the need for Black social change in American social discourse and public policy; engaging a broad base of the Black community and other allies around an aspirational vision and concrete demands for change; and developing a broad pipeline of local and national leaders, scholars, activists, organizers, advocates etc. that move this vision forward.

The movie Selma reminds us of a time when the Black community built and wielded the institutional and political power necessary to effect broad scale social change to improve the lives and opportunities for the Black community. The movie was brilliant because it gave a dramatized blueprint of the strategies, tactics and infrastructure of the civil rights movement that were necessary to create historic social and political change to improve the lives of Black people in the US. That infrastructure included Black-led organizations like SCLC that helped craft and frame policy demands and a national agenda; Black-led organizations like SNCC that did deep grassroots organizing in local communities and provided a vehicle for student leadership; and Black-led organizations like the NAACP Legal Defense fund that moved forward legal advocacy in the courts. The infrastructure also included more moderate and more radical organizations that offered different visions for change that complemented the predominant vision. The tactics and strategies included a coordinated and strategic use of direct action and civil disobedience and strategic communications – in particular the use of television to dramatize and communicate the conditions of the Black community and to expand the reach of the issues and win over the hearts and minds of the public.

There are several parallels between the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Lives Matter movement, but also some key distinctions. The brutality of the Alabama state troopers against peaceful protestors in Selma on Bloody Sunday 50 years ago is reminiscent of the excessive force exacted by the police against peaceful protestors in Ferguson, MO last year. The tactics of civil disobedience and sustained protests and marches used in the civil rights movement are much the same tactics adopted by the Black Lives Matter demonstrators/movement today. The use of media and social media to get the message out and win over hearts and minds is similar. However, I think one of the major structural differences between the Civil Rights movement and the Black Lives Matter movement, and most other contemporary efforts seeking broad scale social change in the Black community, is the relatively weak and diminished infrastructure for Black institutional and political power that exists today.

For the most part, we have moved from a national movement during the Civil Rights era to localized campaigns that are forced to take ever-smaller cuts of larger issues affecting the Black community. We have moved from having a pro-active agenda for broad and sequential change to reactive and episodic moments of disruption and small wins. We still have a wealth of leaders at the local level, but our leaders on the national level tend to be spokespeople often without an accountable base of support in the community that they speak for. Our once strong and powerful national organizations and infrastructure have a greatly diminished influence on national and local policy. Our ability to frame and articulate the need for Black social change has literally been whitewashed with a litany of memes (e.g., reverse racism, criminalization of Black youth, post-racial, political correctness, etc.) in a successful effort to delegitimize the continuing need for Black social change in the hearts and minds of the public. Black arts and media that once provided social critique and analysis has become commodified and stripped of most of its political/critical substance.

Although there are a number of organizations that organize and advocate for change in the Black community today, many of these organizations are severely under-resourced in terms of money and staff capacity. In particular, Black-led social change organizations seem to have had a hard time attracting sufficient funding to support their work. Relatedly, the number of Black led organizing and advocacy groups seems to be on the decline in the last few decades, thereby narrowing the pipeline of Black leaders. Finally, while there is a fair amount of work at the local level, and there are still national legacy/civil rights organizations, there aren’t many strong examples of coordinated national agendas and infrastructure for change in the Black community that have a mass following in the Black community.

I may be giving an overly bleak and deficit oriented depiction of the current state of Black social change, because there is a wealth of really good organizations, leaders and campaigns throughout the country that are making a real difference in improving the quality of life for Black people. However, my point is that I would have hoped and expected that the infrastructure and power that the Black community developed during the Civil Rights movement would have expanded, innovated and grown stronger over the last 50 years; however it seems like it has actually shrunk, stagnated and diminished in strength and influence. And as this infrastructure and influence has diminished, so too has our ability to make Black lives matter.

So the question then becomes, what has to happen in order to strengthen the infrastructure for Black institutional and political power to achieve broad social change in the Black community? This is a complex question for which I can at best offer an incomplete answer. But for me there are at least four broad initial bodies of work that should happen. We have to:

- Identify and assess the current state of the infrastructure for Black institutional and political power.

- Begin the process of envisioning a Black social change agenda for the 21st century.

- Commit to supporting Black leadership and the infrastructure for Black political and institutional power for social change.

- Create a social and political imperative for achieving meaningful and broad Black social change.

An important first step would be to get a better understanding of the current infrastructure for Black political and institutional power and how it arrived at the state it is in today. There are various analyses of how the Black-led infrastructure of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements were systematically dismantled and weakened by oppositional forces in the 1960s and 1970s. However, it would be important to have an assessment of the current infrastructure for Black institutional and political power that examines the strengths, weaknesses, gaps, and opportunities for growth. This research should also provide a scan of the actual landscape of organizations, institutions, leaders, intermediaries, issues addressed, scope and scale of the work, etc. Kevin Ryan of the New York Foundation has been conducting a research project, on a shoe-string budget, to identify Black led organizing groups across the country. This study and other efforts need to be funded at sufficient levels to maximize the data and analytical impact of this work. It would also be important to do an assessment of how Black-led social change groups are funded, at what level, as well as a separate analysis of the propensity, or lack thereof, for institutional philanthropy to support Black-led social change groups. Prior research has shown a significant disparity in the percentage of minority led organizations funded by private philanthropy compared to white led organizations. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this pattern is as bad, if not worse, for Black-led social change organizations. At the same time that we are exploring the current infrastructure, it would be important to begin envisioning what a powerful 21st century infrastructure for Black institutional and political power would need to and could look like. While it is important to look back to the Civil Rights movement for inspiration and critical lessons, it would be a mistake to simply try to replicate and emulate that infrastructure today. We operate in a different institutional, technological and social environment today, which will continue to evolve and we need to build an infrastructure that makes the most of the current context and that can innovate to set us up for the next 20-30 years.

While structure is important, the most essential part of this visioning would be to answer the fundamental question of what does the Black community needs in order to thrive. Envisioning a Black social agenda during the Civil Rights movement was challenging, but also more straight-forward than it would be today because the deprivations and disparities during the Civil Rights era were so stark. However, in the current era, where progress has been made for many, but not most Black people, what should a Black agenda for social change look like; how do we ensure that all voices are included and exert leadership; what are the most impactful and specific demands for change; and what are the most effective strategies? The profound complexity of this task requires that this be a communal and community building process where a broad cross-section of the Black community is engaged, rather than just the intelligentsia or institutional leaders. These conversations need to become part of the daily life of the community and held throughout the Black community in organizations, churches, barber shops, hair salons, schools, community centers, street corners, on social media, in academia, on radio, in magazines, on television, etc. But for this to happen, there needs to be strong institutional and organizational infrastructures to catalyze and propagate these conversations, and more importantly to distill the ideas into an actionable agenda for contemporary Black social change.

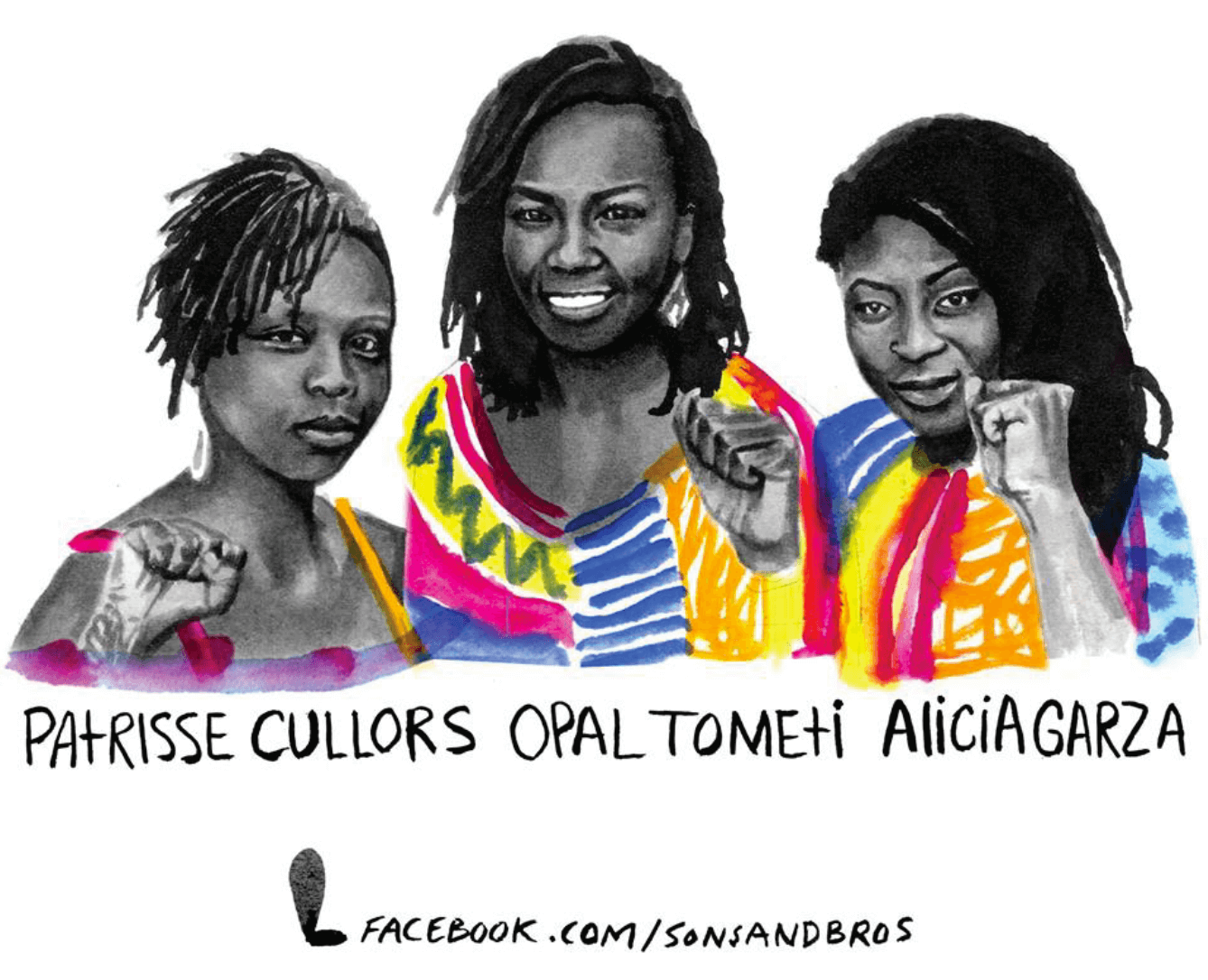

Perhaps the most fundamental thing that needs to happen to build and strengthen the infrastructure for Black political and institutional power is for more people to commit to building and strengthening the infrastructure for Black political and institutional power. Skilled, trained, committed and connected leaders are the most valuable resource for any infrastructure and movement. Therefore, one of the most essential investments to make in strengthening the infrastructure for Black political and institutional power is to invest in developing Black social justice leaders. A great example of Black social justice leadership development is an organization called BOLD (Black Organizers for Leadership and Dignity). BOLD is a national program designed to help rebuild Black social justice infrastructure in order to organize Black communities more effectively and re-center Black leadership in the US social justice movement. BOLD has trained and connected dozens of Black social justice leaders, including the three Black women who created Black Lives Matter, who actually met through the BOLD network. But as with other parts of the infrastructure for Black social change and power, BOLD is not sufficiently resourced and thus cannot maximize its full potential for effecting social change for the Black community. In supporting Black leadership today, we have to recognize and embrace that it will often look different than the leadership that we have seen before. As the BlackLivesMatter website states, the Black leadership of today will more fully represent youth and young adults, women, queer, trans people and all people along the gender spectrum, people with records, the disabled, the undocumented, etc.

Finally, we have to re-create a social and political imperative for Black social change. The powerful conservative backlash against the Civil Rights and Black Power movements has systematically weakened Black-led infrastructure and created an infrastructure and social milieu that effectively delegitimizes, marginalizes and vilifies anyone and any effort that tries to speak assertively about structural racism and the legitimate need for equity, justice and opportunity in the Black community. There are scores of Black organizational leaders today that are working to improve conditions in the Black community, but many of them feel they can’t assertively say they are trying to build power for the Black community or combat racism for fear of being ostracized by their funders, colleagues and decision-makers. As mentioned above, we need to re-create an imperative for Black social change in this country, but this will take some time. In the meantime, we need people to be courageous, take the risk and commit themselves personally and professionally to building the infrastructure for Black political and institutional power and to combatting structural racism.

There is a special need for this courage and commitment within philanthropy because this sector can help to make sure that this infrastructure is resourced and connected at the level that it needs to be effective. Foundations and individual donors have to prioritize investing in Black leadership, Black-led organizations for social change and in building the infrastructure for Black institutional and political power. Also, there needs to be a fundamental shift in the practice of philanthropy that prioritizes work to dismantle structural racism and recognizes that the persistent and pervasive nature of structural racism will require perpetual and substantial investment and commitment to dismantle.

***

This year we celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the passage of the Voting Rights Act. It is important for the country to mark the anniversary of this historic milestone in the Black community’s struggle and legacy for equality and justice in America. However, we can do more than just commemorate this milestone, we can chart a new path and organize to build the political and institutional power we need to secure new milestones in the journey for Black freedom, justice and equity. We must answer the call to make Black lives matter more in every aspect of this society and for the Black community to have a greater opportunity to thrive as a whole. The Black Lives Matter movement has created space for meaningful dialogue and action and allowed an opening to assert the need to build a powerful Black infrastructure for change. This is a once in a generation moment, as the 50 years in between Selma and Ferguson should illustrate. We must seize on this moment and opportunity to build a lasting and powerful infrastructure for Black social change and to dismantle structural racism. If we do this, then we will make Black Lives Matter today, tomorrow and forevermore.

1 See this link for a description of 21 people of color and/or mentally ill people killed by police in 2014 – http://thinkprogress.org/justice/2014/12/12/3601771/people-police-killed-in-2014/.