September 25, 2020

It’s impossible to take the violence out of policing

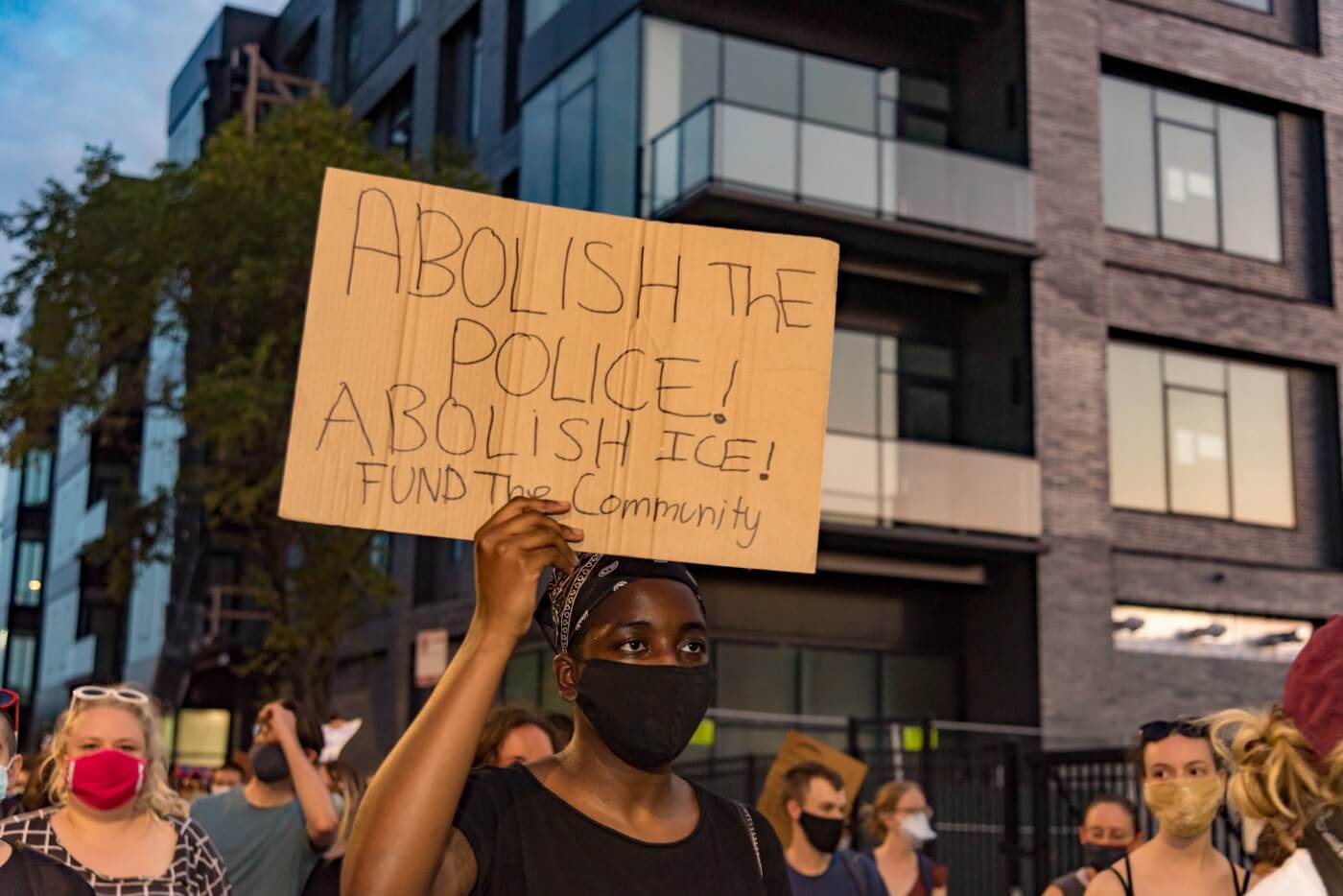

Once again, there is justified outrage at police acting to kill with impunity. I understand the anger and also feel rage. The lack of concern for Black life, though unsurprising, remains gutting. And yet, I hope that we’ve finally arrived at a moment when more people interrogate why so many of us continue to demand that the police stop being the police.

“Why do the police keep murdering Black people and others with impunity?” simply isn’t a good question. Policing has to be racist, patriarchal, ableist, homophobic, and transphobic to meet its purpose. If you want to maintain a white supremacist, cis-hetero patriarchal, capitalist state, then particular groups have to be targeted, controlled, and contained. This leaves us with nowhere to go and very little to do.

We need better questions and better demands. Both are within our reach — and so is the possibility of achieving police abolition.

Trust Me, Minneapolis Is Right to Defund Its Police Force

I spent 18 years as a police officer, and I know anti-bias training won’t be enough

gen.medium.com

A better question to ask is, “What do we need to do to stop police from killing Black people and others with impunity?” We can start by reducing people’s contact with police altogether. We can defund police departments and invest in our communities. How do we do these things? That is a generative question which might get us closer to true public safety.

Have people been offered a vision of public safety that doesn’t include police? If not, why not? The fact that police abolition is unthinkable to so many people is profoundly dangerous. It means that police have so thoroughly colonized and dominated our thinking that we are unable to even imagine a world where they don’t exist. The fact is that we haven’t always had police. What makes us believe that we always will — or that we always will have to?

It’s not simply that we can’t imagine a world without police, but that we are disciplined into not having that imagination. Cop shows and other pro-law enforcement propaganda are an important way of naturalizing policing. Children’s books, cartoons, comic books, Lego toys, Officer Friendly programs in schools, and other popular culture artifacts past and present — all condition us into being unable to imagine a world without police. Cops are lionized in monuments, memorials, and highway signs. Cops are usually portrayed as heroic. We’re told that they are the bulwark between order and complete chaos. It’s hard to think of any other occupation that approaches this type of public relations effort. Why does law enforcement need so much advertising? There are no television shows uplifting the contributions of child care workers, but they are essential to ensuring the functioning of modern society.

If you care about the violence of policing, then you should want as little policing as possible in any form.

Law enforcement is always at work to preserve its legitimacy. It is constantly reinventing, inserting, and reimagining itself into new roles. But the fact that its members must constantly create propaganda to defend their position in society suggests that perhaps their role in our culture is more precarious than it appears and that they are in fact vulnerable to public pressure and organizing.

This offers us a real window of possibility in our abolitionist organizing strategies. Such a strategy must aim to reduce contact with police without increasing the legitimacy of policing. If you care about the violence of policing, then you should want as little policing as possible in any form. You wouldn’t want to keep legitimizing policing as a response to various societal problems. We cannot, for example, call for reformist civilian review boards that actually serve to entrench police power. Similarly, we cannot call for social workers to replace police if they’re imbued with the same mandates of surveillance and coercion. An abolitionist organizing strategy shrinks the prison industrial complex without increasing its legitimacy.

Over the past few years, criminal “justice” reformers and some academics have suggested that marginalized communities are both “overpoliced” and “underprotected.” Police patrol and surveil their neighborhoods ubiquitously, and yet may or may not respond to calls for aid in moments of crisis. The “overpoliced and underprotected” framework, however, is flawed. It belies a fundamental misunderstanding of the purpose of policing. Here we can learn from political theorist and activist Frank Wilderson, who has said, “I’m not against police brutality, I’m against the police.” Violence is an inherent part of the police and policing. The police monopoly on the use of force is not tangential or incidental; it is constitutive. That means we won’t be able to excise just the “violence” part of police violence while preserving the rest. Violence is central to police work. Another question raised by this framing is: “What is the threshold for the right amount of policing?” Are we supposed to adopt a Goldilocks strategy to determine this? What marginalized people experience is not bad policing: It is simply policing. It isn’t too much or too little — and it will be never just right.

As for the “underprotection” argument: It assumes police failing to protect marginalized people is a bug rather than a central feature of policing. In fact, one could say the symbolic efforts at “protection” that police half-heartedly perform to address marginalized people’s calls for assistance and support are simply a strategy to preserve police power. Marginalized people are led to believe that state protection is within reach, and therefore, remain invested in the preservation of police and policing, which is to say, state-sanctioned violence.

During a virtual teach-in in June, writer Patrick Blanchfield suggested that the police “are in our minds as a solution rather than as a problem.” This is an important insight that should shape the focus and direction of our organizing. Too many people continue to see police as a resource to end violence rather than as significant purveyors of violence in our communities (and escalators of violence at protests). We have to actively help people divest from the idea that policing keeps us safe and that policing was developed to address public safety in the first place. Abolitionist organizing insists that we focus on divesting, investing, and experimenting. All three are important steps.

Whenever prison industrial complex (PIC) abolitionists call for the elimination of policing, people immediately and aggressively push back by insisting that we provide “an alternative” to address public safety. The question hurled at us is, “Well what will replace the police?” The answer is that no lone entity will or should replace prisons, policing, and surveillance. I think about words I read recently from a Chicago-based organizer: “When I see police, I see 100 other jobs smashed into one thing with a gun.”

Police are currently the catch-all for addressing every social problem as the state has and continues to defund the commons. Different kinds of harms need different kinds of responses. An inherently violent institution, one whose state-sanctioned freedom to use violence as its constitutive and unique source of authority, should not be one of these responses.

Rachel Herzing, a long-time PIC abolitionist and executive director of the Center for Political Education, a movement-building organization, often says that “eliminating the PIC will expand the context in which we can develop new ways of relating, build protection, and address harm.” At present, policing takes up so many resources and so much space that it actually crowds out opportunities for community-based solutions for addressing harm. Those community-based solutions are always under- or un-funded. Some of these solutions are actively undermined by the police.

We can organize toward the elimination of policing while we attend to our communities’ immediate needs for safety. But having those needs for safety met shouldn’t be the prerequisite for demanding abolition of the prison industrial complex. As conceptualized by Norwegian sociologist Thomas Mathiesen, abolition is an alternative in the making. It pushes us to break with the current order, to refuse, to say, “We don’t want this,” while simultaneously forging new ground and building a different world.

This is where hope lies. It lies in a vision of a world where we have everything we need to live with dignity and where safety is not achieved at the tip of a gun.

WRITTEN BY

Founder/Director Project NIA (@projectnia), Co-Founder (@chitaskforce) & (@ChiFreeSchool), Abolitionist, Organizer, Educator, Curator, Hallmark Channel watcher