Right to the City Alliance – March 2015

Wall Street, the financial center of the most powerful city in the world, was built and maintained through slave labor. The massive profiteering of big banks and private equity firms that prevails, rides on the backs of black and brown families. Movements across America confronting the crisis of foreclosure, gentrification and displacement, need to have black leaders who help define the vision for our right to the city.

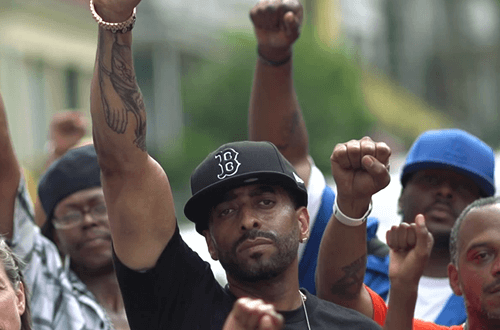

Here in the United States, the recent momentum built in the fight against state violence and for a world where #blacklivesmatter has given new spark to all of us. We have been energized by this opportunity to deepen the level of dialogue amongst our base, supporters and larger movement family about history, strategy, structural inequality and how to strengthen the connections between struggles for social, economic, environmental, and racial justice. The spirit of openness and honesty that this historic moment provides allows us to stretch and make connections beyond our immediate needs and interests. That’s how strong movements are built. We’re seeing this kind of stretching happen all around us as we witness this movement of black and brown youth rising up to articulate issues of racial inequity.

Working to win a right to the city for all puts us in direct opposition with the process of urban restructuring (popularly known as gentrification) that the free market enforces on our communities. It’s a process that is heavily reliant on the policing of working class, black and brown communities to impose destabilization and displacement. Police violence – and the threat of it – is an intimate part of our daily lives.

Making amends for the systematic historical violence – physical, economic, social and psychological – inflicted on black communities requires no less (but plenty more) than a complete transformation of our economic and political structures.

According to the Nation magazine’s piece, “We’ll Need an Economic Program to Make Black Lives Matter”, “In 1966, along with A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and other organizers and scholars, Martin Luther King Jr. released the now all-but-forgotten Freedom Budget for All Americans, which included full employment, universal healthcare and good housing for all. “The Freedom Budget is essential if the Negro people are to make further progress,” he wrote. “It is essential if we are to maintain social peace. It is a political necessity.”

Ta-Nahisi Coates’ recent article in The Atlantic brilliantly articulates his Case for Reparations by illustrating the racist history of housing policy in the Unites States.

Having been enslaved for 250 years, black people were not left to their own devices. They were terrorized. In the Deep South, a second slavery ruled. In the North, legislatures, mayors, civic associations, banks, and citizens all colluded to pin black people into ghettos, where they were overcrowded, overcharged, and undereducated. Businesses discriminated against them, awarding them the worst jobs and the worst wages. Police brutalized them in the streets. And the notion that black lives, black bodies, and black wealth were rightful targets remained deeply rooted in the broader society. Now we have half-stepped away from our long centuries of despoilment, promising, “Never again.” But still we are haunted. It is as though we have run up a credit-card bill and, having pledged to charge no more, remain befuddled that the balance does not disappear. The effects of that balance, interest accruing daily, are all around us.

In a place like Ferguson, we can see how the impact of the relationship between predatory lending, the foreclosure crisis, criminalization of youth of color, and a general upsurge in racial profiling by the police force can cause widespread feelings of disinvestment and futility in the current system and it’s function in protecting and serving them. As stated in a Bill Moyers’ special, “Nationally, 17 percent of homeowners are underwater — they owe more on their mortgages than their homes are actually worth. In Ferguson, that figure sits at 50 percent. Because so many homeowners are struggling, the town is ripe for institutional investors.”

As we see a growing rise of renters and struggling homeowners across America, we know that black and brown families are suffering with rising rents and falling wages the most. We know that they are at the highest risk in losing their stake in the American dream and the right to the city.

Organizations in the right to the city network and beyond, all over the country, have been embracing the idea that #blacklivesmatter. Right to the City (RTC) emerged in 2007 as a unified response to gentrification and a call to halt the displacement of low-income people, people of color, marginalized LGBTQ communities, and youth of color from their historic urban neighborhoods. This may seem only like a fight for land and housing for black and brown communities, but it is a fight to make sure that we are aligned with a mission that says we need our memories, our culture, our neighborhoods, our art, because black lives matter.

Former RTC Steering Committee Chairperson and co-creator of #blacklivesmatter Alicia Garza discussed the emancipatory impact of black liberation in her Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement:

When Black people get free, everybody gets free. ” #BlackLivesMatter doesn’t mean your life isn’t important–it means that Black lives, which are seen as without value within White supremacy, are important to your liberation. Given the disproportionate impact state violence has on Black lives, we understand that when Black people in this country get free, the benefits will be wide reaching and transformative for society as a whole.

As an alliance, Right To The City exists to amplify the voices of people who are most-impacted by structural inequality, expressed in the call to Reclaim, Remain, Rebuild our cities to ensure Homes For All. This is about both strategy (people with the most investment in changing things will take the strongest leadership in doing so) as well as values.

Expressing love, support and solidarity with Ferguson or NYC protesters (or sisters and brothers in struggles for justice anywhere) is about fighting white supremacy and capitalism, and bringing power into our hands and communities collectively. It isn’t about hating or discriminating against white people, or spreading our already-limited capacities thinner, by taking on issues not directly related to expanding truly affordable housing.

This is about actively addressing our country’s history of structural racism, specifically anti- black racism and expanding the way we think about state violence to include how our current economy is and has historically been violent towards black lives. This is connected to housing, democracy and all the other foundations of a true right to the city. And above all, it’s about honoring a new generation of young people seeking to find solidarity, support and resilience through our movement.

In this time, there needs to be a clear sense of equality in how we care for and empathize with each other. As scholar Orisanmi Burton put it,

You see, the brilliance of the “blacklivesmatter” rallying cry is that it is addressed, not to the perpetrators of state violence, nor to their supporters, but to the movement itself. It is addressed to black people and to non-black allies who recognize that their destinies are linked by a common fate. Those who stand arm-in-arm, blocking traffic, are saying, “black lives matter to us.” That black lives have no value to the state is as clear as (Officer) Darren Wilson’s conscience.

We know that to build a society in which black lives truly do matter, communities need democratic control over the resources needed to produce safe, equitable, nourishing, livelihoods. This is an inextricable part of our collective cry for a right to the city.